Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 04/06/25 in Posts

-

Just had in a very nice thin Patek pocketwatch. Came in for a staff; found out it had a random staff installed along with a random roller table- it didn't even engage with the fork. And best of all, a tooth was broken off the escape wheel. It was extremely lucky that I had an escape wheel in my stock that was the correct diameter, also found a roller table that was able to be modifed and work very well with the fork, and made a new staff. Darn thing runs great now- around 270 flat, 30 degree drop in verts. At least the former watchmaker did no permanent modifications.6 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

Actually, it is easier to drill the brass in the steel hole. At some point, the piece remain will get out. No need to make the pin in lathe. Use tapered pin like one for hairspring pinning. One is easy to prepare out of brass wire with close diameter.3 points

-

For this reason, I believe that every video should begin with a clear disclaimer stating that viewers should not assume the content reflects best practices and that the content is primarily intended for entertainment. My approach may come across as unnecessarily harsh, but this is to prevent those poor souls who actually want to learn and develop their knowledge and skills from being misled into thinking they've found an educational channel. Why do I care, and should I care, you might wonder. Well, because servicing and repairing movements is complex and challenging enough without the enthusiastic beginner having to struggle with methods that can unnecessarily lead to failures and various inconveniences. That said, most channels seem to offer a few golden nuggets, but to understand what a golden nugget is and isn’t, you first need to have a reasonably solid and sound foundation to stand on, and that foundation is not easily found on many YouTube channels. It’s true, but I generally regard Mark as an exceptionally knowledgeable and skilled repairer, and this is probably the exception that proves the rule. I can’t recall seeing anything else he has done that is even remotely "blameworthy." I have no problem turning a blind eye to this.3 points

-

The diamond graver is the correct one did you use the graver diamond up or diamond down because how you present the graver to the work is different as is how you present it to different materials . Brass & bronze needs natural or positive rake whereas steel needs negative rake & the graver needs to be very sharp but a blunt graver will cut soft aluminium quite easily. Have a look at one of my videos, I don’t profess to be an expert but I do get the job done, also a lot of people say you need speed when using a graver but I don’t agree because to much speed can lead to work hardening making it difficult to cut what is needed is good torque, you will see from my video I run the lathe quite slow but it still cuts very well the steel is EN1. try altering the angle that you present the graver to the work & make sure the graver is sharp also practice practice practice. Dell3 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

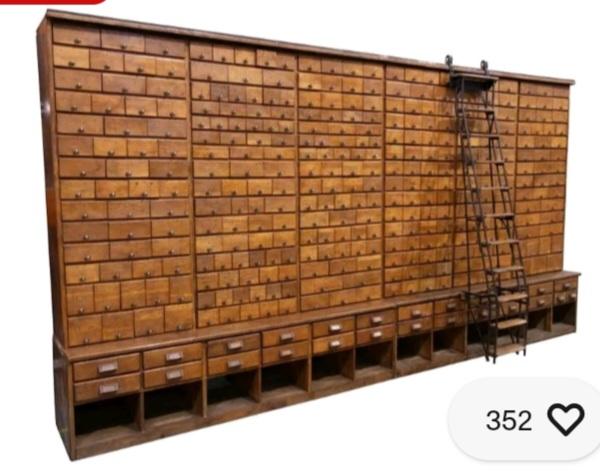

Zip lock bags are the cheapest and optimise the space you have. The parts stored on the mainplates if you have them, which provides the best protection. I write the caliber info on the bags then keep them in plastic chinese takeaway tubs, in brand alphabetical order ( all the A, s together, all the B,s together etc ) My wife reminds me of how sad I am, it doesn't feel that way in my head though . You then need a hardback note book to list them in, making any notes of what is missing on the plate, saves you digging through the tubs, to see if you have a required donor and the part required. If you do this from the start it will save you a lot of time later on going through them. For small individual parts on their own, do as has been done for decades , clear gelatin capsules. Here is a drawer ready to start filling up.2 points

-

2 points

-

When I need to make screw, I use soft У10А, which is russian steel, very similar to O1. I would use O1, but for me it is harder to source because of the place I live. When I need blue steel, I usually temper to blue rollers from roller bearings. When turning blue steel with HSS gravers, You will not only have to resharpen the graver, but to sharpen it often (several times while turning). This is not only sharpening, but polishing too. I find for myself carbide gravers are much better, but this is personal and one will find for himself what serves better for His needs. High speed (revolutions) is not needed as the friction will cause heat and heat can make the work to harden and the HSS graver to get dull. If You notice the graver is not cutting well, then sharpen it immediately. Blue steel is easy to work harden with dull graver and it is hard to get rid of the hardened portion, especially with HSS graver. Work hardening has nothing to do with heat/quench hardening, it is rather due plastic deforming on the surface by dull graver or drill bit.2 points

-

The important rpm would be the headstock turning speed, motor rpm doesn't matter. It's how fast the workpiece is spinning. Once you get to know what a sharp graver is and how it cuts ,then you will know when to sharpen it. Absolutely Cees , my best brass shavings are produced at ridiculously low speeds, steel higher but still quite low. A keen edge makes all the difference.2 points

-

When using steel that hardens easy, like O1, you have to be careful not to heat it when turning. This will "work harden" it and you might damage your die anyway when cutting threads. When using sharp gravers, you'll find that you don't need high rpm's. Low rpm's and sharp cutting edges will keep the temp low.2 points

-

It doesn't seem to have any stumps etc, is that still a good price? It comes up in English for me. Just looked them up, indeed a good price.2 points

-

See here: https://www.watchrepairtalk.com/topic/28465-what-is-this-plastic-thing-on-tissot-caseback/2 points

-

I think it unscrews to come off, so to provide access to regulator/adjust arms, without having to remove the case back.2 points

-

2 points

-

His videos should be looked at as entertainment not as an instructional video. So as long as you look at it as entertainment and not as an instructional video you'll be fine.2 points

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I just managed to open the back, and you are right, the back one is the one you pointed to.1 point

-

1 point

-

Idiots going made with solder, clock weights of the wrong size to get the clock to work. bad re-bushing such as protruding bush because the pivot has worn or broken, pallets bent to get the thing to escape. All this and more I have found in clocks. I would like to hit the buggers over the head with a rubber mallet.1 point

-

Thank you, everyone, for the answers. I have bought some small storage boxes and I have everything sorted by movement (more or less). For future repairs, I will make sure everything is correctly stored.1 point

-

1 point

-

I finally got my lathe up and running, and I tried turning a few pieces by hand. I needed to create an M0.6 dial shoulder screw, so first I practiced on a piece of aluminum. And since aluminum is so soft, I was able to turn down the diameter using a Vallorbe diamond-shaped graver pretty quickly. I acquired a bit of confidence in using the graver, so I decided to try on steel. I would normally try on O1 tool steel since it's comparatively soft, inexpensive, and hardens well, but I didn't have any. I do have some pivot blue steel, so I tried on that first. I also have some A2 steel, which I tried as well. In both cases, it took me so long to turn down 3 mm into 0.6 mm (and then on top of that, I overpowered the piece and ended up breaking off what was supposed to be the threaded portion ). So I'm wondering if my technique is incorrect, or if I'm using the incorrect type of graver, or if something else. Thanks!1 point

-

This site might be helpful. I used to teach a technical class (twice a year) in Berlin 35+ years ago. I could kinda sus out a little German to get along while there. It is all gone now. So Frank will have to help us.1 point

-

The Poljot Sturmanskie Chronograph: The Soviet-Era Pilot’s Watch You Didn’t Know You Needed When you think of legendary pilot’s watches, your mind probably drifts toward the likes of the Rolex GMT-Master, the Breitling Navitimer, or perhaps even the IWC Big Pilot. But if you’re here, chances are you’re the kind of person who enjoys veering off the well-trodden horological runway and landing somewhere a little more... Soviet. Enter the Poljot Sturmanskie Chronograph—an exquisite piece of Cold War-era timekeeping that blends rugged functionality with just the right amount of vintage charm. Also, I accidentally bought one. But we’ll get to that later. A Brief History Lesson (or: How the Soviets Decided They Needed Chronographs Too) The Sturmanskie name has long been associated with Soviet aviation and space exploration. Famously, Yuri Gagarin wore a Sturmanskie when he became the first human in space in 1961—though that was a simpler, time-only model. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union decided that their air force pilots needed something more complex: a proper chronograph. Enter the Poljot 3133 movement, a robust and slightly “borrowed” (read: reverse-engineered) take on the Swiss Valjoux 7734. In true Soviet style, they took a reliable Western idea and made it their own, producing a movement that has since developed a cult following. The Sturmanskie Chronograph became standard-issue for Soviet pilots, cosmonauts, and, I assume, the occasional KGB agent who needed to precisely time how long it took to shake a tail in a black Volga. First Impressions: Rugged, Functional, and Gloriously Soviet When my Sturmanskie arrived, I’ll admit, it wasn’t planned. I was dabbling in the fine art of eBay late at night, bidding on a job lot of watch parts, when—whoops—I also won this. But fate works in mysterious ways, and honestly, I couldn’t be happier. The moment I unboxed it, I knew this was something special. The dial is a masterclass in military functionality—no-nonsense, crisp Arabic numerals, and subdials positioned in a way that suggests this thing means business. There’s a tachymeter scale around the outer rim, which, if I’m being honest, I will never actually use unless I suddenly find myself timing a MiG fighter’s landing approach. And then there’s the case. At around 38mm, it’s smaller than many modern pilot’s watches, but let’s be real: if you need a 44mm wrist-clad dinner plate to feel like a real man, you may have other issues to address. The domed acrylic crystal only adds to the vintage charm, with just enough distortion to make you feel like you’re reading your watch through a Cold War-era submarine periscope. The Movement: A Soviet Workhorse with a Swiss Accent Inside the Sturmanskie ticks the Poljot 3133, a movement that started its life in the 1970s and is still revered today for its durability. It’s a manual-wind chronograph, which means you have to give it a daily wind—an act that adds to the whole experience. There’s something satisfying about winding a mechanical watch, knowing that you’re directly interacting with decades-old engineering. Accuracy? Let’s just say that it’s probably not COSC-certified, but that’s part of the charm. If you wanted pinpoint precision, you’d buy a quartz Casio and call it a day. Instead, the 3133 offers a pleasingly anachronistic experience, reminding you that timekeeping is as much about the journey as it is about the destination. How Does It Wear? Despite its military roots, the Sturmanskie is surprisingly comfortable. The case sits nicely on the wrist, and while the original strap was probably made from surplus Soviet tank leather, swapping it out for a leather band transforms the watch entirely. It’s one of those rare timepieces that looks equally at home in a bomber jacket or peeking out from under a dress cuff—assuming your workplace is cool with you showing up in Cold War-era memorabilia. Comparisons: How Does It Stack Up? Now, let’s put the Sturmanskie up against some of its contemporaries. Compared to the iconic Seiko 6139 “Pogue,” the Sturmanskie has a more traditional layout but lacks the automatic convenience of the Seiko. The Omega Speedmaster, its better-known spacefaring cousin, is undeniably a superior watch in terms of finishing and precision, but you’re also paying an entirely different price bracket for that privilege. And against something like the Heuer Bundeswehr Chronograph? The Sturmanskie holds its own with its military pedigree, even if the Heuer has that undeniable Swiss allure. Final Thoughts: A Piece of History for Your Wrist The Poljot Sturmanskie Chronograph isn’t just a watch—it’s a piece of Cold War history that you can wear. It’s functional, it’s charmingly imperfect, and it’s a fantastic conversation starter. While it may not have the cachet of a Rolex or the refinement of an Omega, it offers something arguably better: character. And, if you’re anything like me, it might just be the best accidental eBay purchase you’ll ever make.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Welcome to the forum It'll be a Ronda 763 which takes a 364 battery and then a Chronograph module which we'll need to see photos of. Edit So the full details are it's a Gucci 012.839R so the other battery would be a 377.1 point

-

In that case I'd be looking at returning it as there's no reason a new movement shouldn't work.1 point

-

Good price, the stakes and stumps look very clean and the extended base is a great addition to the tool. The other anvil is curious , maybe from another tool or like Frank said usable on top of the pin held one or on its own.1 point

-

The word “ serviceable” means that looked after and properly used and not abused it should last you for a long time. These are precision instruments and should be treated as such. ie. Cleaned and oiled occasionally and not used for onerous tasks.1 point

-

@Nucejoe @Kalanag Thanks very much for the info - and sorry for the duplicate post.1 point

-

That's extremely nice. You guys will certainly hear from me again. PS: love your Youtube channel!1 point

-

The classic - Practical over Theory - A book doesn't cover every situation.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I agree with the advice above, everything you have there looks to be worth keeping. There is the possibility of using the parts, screws and jewels in future repairs. Wheels are useful when learning to use the Jacot tool. You will inevitably snap some pivots, so it’s best to learn on wheels you can afford to damage. You can also practice other new techniques on these parts, such as reaming out a hole and fitting a friction fit jewel. Best Regards, Mark1 point

-

Cousins has an aluminum case with a bunch of small circular aluminum canisters with glass tops. I keep dead movements in those. Like movements together. Assembled as far as they'll go. Jewels, screws, springs, and who knows if you'll come across another of the same movement needing attention, or a forum member needing a part.1 point

-

Let me rephrase my previous response to VWatchie's findings. As far as I am concerned ; " whatever end shake you get best overall performance with, is the ideal end shake " which mainly applies to balance shake and entire escapement. Though VWatchie only mentions erratic graphical display ! I presume the word "overall includes , timekeeping, minimum amp drop after 24 hrs run, smallest delta " positional amplitude drop" etc. When we get optimum performance, I can't care less what books recommend. The issue OP is facing is a problem in gear train, which I think this thread will well cover all possible faults and approaches to correct the problem. Regs1 point

-

I threw some watch parts from a pin pallet movement away yesterday and whilst it was hovering over the bin ready to go in I had a strange feeling of 'What are you doing!' I overcame it thankfully and in they went, but I did keep the screws and jewels. Always keep screws and jewels! Incidentally, this was the very first time I've thrown watch parts away, because I have 'the hoard'. It can be a nasty little affliction1 point

-

One can only concur with the previous posts, I have quite a lot of redundant watch and clock bits. Never know when you might need them.1 point

-

Never throw away anything with good jewels. Odd wheels? You can practice pivot burnishing in the future.1 point

-

Keep everything !!! It's all usable. Reassemble it and zip lock it whole. A plate, a bridge or a cock might hold a jewel that you will want one day.1 point

-

Never ask anyone into watchmaking what to keep! As Andy points out we probably all have an aversion to getting rid of potentially “useful “ things natural born hoarders and tool collectors, every single one of us Tom1 point